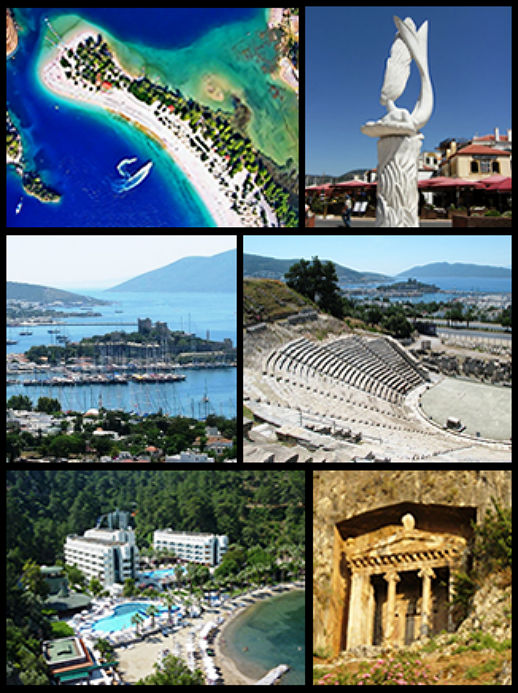

Located in one of Turkey’s primary touristic regions, Muğla continues to preserve its historic texture even today.

A threshold is a boundary between where one is and where one is going. An intermediate place, a place of uncertainty. Alternatively, it is a transitional place that sustains the hope of going from one location to another. Some cities are such transit points; one passes by them but for some reason never stops off, never wanders through, and they wait instead on the threshold like people life has passed by. Muğla is such a city.

Muğla is an artery with links to resort towns such as Bodrum, Dalaman, Datça, Fethiye, Kavaklıdere, Köyceğiz, Marmaris, Milas, Ortaca and Ula. Which may explain why it is always propelling travelers to its adjoining capillaries. Nevertheless, with its old, two-door, two-chimney houses, the historic texture of its streets, its handful of surviving traditional handicrafts and Turkey’s only museum of natural history, Muğla is not a city to be passed over lightly.

SURVIVING UNSCATHED

Muğla province, which includes Bodrum, Fethiye, Marmaris and Datça, is Turkey’s largest holiday and touristic center after Antalya. A modest looking town, Muğla is situated on a plateau overlooking Milas Plain. Its history goes back to 3000 B.C. But the known history of the region, which was called Caria since the Carians settled there in ancient times, begins with the Hittites. Called Lugga by the Hittites, the Muğla region later passed under the rule of the Phrygians, the Lydians, the Persians and the Byzantines.

Incorporated into the Ottoman lands by Sultan Bayezid I in 1391 and liberated in 1921 in Turkey’s War of Independence, Muğla is a unique city 670 meters above sea level, nestled in the foothills of Mt. Hisar, an interesting looking mountain with a flat top. Its uniqueness derives as well from the preservation of its historic texture. Unlike the luxury touristic centers that surround it, Muğla has not compromised its traditional fabric, and although it embarked on a rush to ‘urbanize’ with the founding of Muğla University, it still boasts a large number of streets that preserve their original appearance. For the designs of Muğla houses continue to constitute a unique model for Turkish traditional architecture with their elaborate wood workmanship, decorative ceilings, and the chimneys that have become an icon for the city. These old Muğla houses are concentrated in the city center, especially in the foothills of Mt. Hisar, between the district of Karabağlar in the highland of the same name, and Dügerek on the slopes of Mt. Yılanlı.

“SABURHANE: HEART OF MUĞLA”

If you’d like to take a journey through the history of Muğla, you must definitely go to Saburhane. In this district, located in the city’s eastern sector in the southern foothills of Mt. Asar – another mountain with a broad, flat top that you can reach by following the old riverbed – have a seat if you like in one of the coffeehouses covered with grapevines in the center of the square, and lose yourself in the mists of time among the old Greek and Turkish houses.

The first settlement in the area in the 4th millennium B.C. began during the migrations back and forth between eastern Greece and the coast of Asia Minor. Although several colonies were founded on the Achaean, Carian and Ionian shores, the Persians wrested control of all of them in 546 B.C. Coming later under the rule of Alexander the Great, the region remained within the boundaries of the Kingdom of Rhodes and the Eastern Roman Empire. When the Ottomans appeared on the scene they decided to settle both Greeks and Turks here. While the Greeks operated mills, carpentry shops, bakeries, baths and tailoring establishments, the Turks engaged in farming and raised livestock.

Although the Greeks emigrated in the population exchange that followed the founding of the Republic of Turkey, the homes they left behind have been preserved intact. Settling at Saburhane and Konakaltı, the Greeks built stone houses in a style befitting their own culture. A fundamental characteristic that distinguishes them from Turkish houses is that they stand in solid rows, their facades flush with the street without courtyards. Another distinguishing feature is that they are built of cut stone. The clock tower that you can see in the Arasta, the center of manufacturing and trade in the old city, is a marvelous memento built by the the Greek master Filivari in 1895.

If you see double-doored, double-chimneyed houses as you stroll through this district, remember, these are the Turkish houses. Extending especially in the direction of the foothills of Mt. Hisar, these houses constitute the essence of the traditional fabric, a trio of red tile roofs and white walls overhung with greenery that creates the urban skyline. The typical features of these houses, which represent a certain style with the outbuildings in their courtyards, include an open front hall called a ‘hayat’, courtyard entrances known as ‘kuzulu kapı’, hearths, chimneys, long wide eaves, ceiling decorations, intricately carved wooden verandas, and bathrooms embedded in the walls. Built to be inward-looking like all Turkish houses as a result of the concept of family privacy, they are generally made of stone or, secondarily, of timber. All the weight-bearing walls, courtyard walls, and the ground floors especially are constructed of broken, unhewn stones held together with limestone mortar; their roofs are covered alaturca-style with tiles. The key feature of the chimneys that are a virtual symbol of Muğla is that they are made of exactly 52 of these local tiles. Their interesting doors are another distinguishing characteristic of Muğla houses. Houses are entered through wide, double-panelled ‘kuzulu’ doors which are high in keeping with the 2.3 meter-high courtyards walls. If you proceed from Saburhane to the Arasta, you’ll encounter Muğla’s old market and shops where a handful of saddlers, blacksmiths, ironsmiths and tinkers are struggling to keep their crafts alive today. If you want to buy a gift, be sure to stop at the newly restored Yağcılar Khan.

TASTY DISHES

If some intriguing aromas come wafting up as you stroll through the streets, you can be sure it’s time to eat. ‘Tarhana’ tops the list of dishes unique to Muğla, which offers a number of highly interesting alternatives in terms of the local cuisine. Olives and dried peppers constitute a cuisine in themselves here. Eating olives in particular have preserved their importance since the days of Caria. There are many restaurants in the market serving the local cuisine. Don’t miss this chance to taste Büryan Kebab, tart Döş Dolma, Börülce and Keşkek. And be sure to sample the local sweet, ‘çıtırmık’, a kind of ‘halva’ made from semolina.

Last but not least, do not leave Muğla without visiting the Natural History Museum, a part of the Muğla Museum. Exhibited here are fossils dating back 5-9 million years ago that were dug up in the nearby village of Özlüce in Muğla province. Fossils of creatures that lived and then became extinct over a broad area stretching from East Asia all the way to Spain. And after you’ve toured the museum, you can sip coffee in one of the coffeehouses under the trees and unwind after a hard day’s sightseeing.

Muğla,