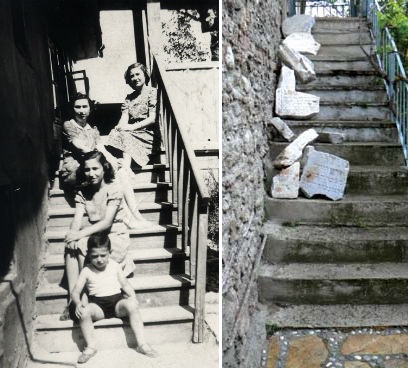

Tombstones engraved with Hebrew letters, recently found in the small courtyard behind the Senora Synagogue, now reston a staircas

The Seniyora (Senora Shul), Synagogue is the most active of the remaining synagogues on Havra Sokak-Kemaralti Izmir is open every morning. It’s a simple but pleasant and interesting building, almost two centuries old, with obvious historic value.

Seniyora Synagogue at number 77. at airy sanctuary, whose dominant color is white, though trimmed with muted turquoise and gold, it boasts a piece of Ottoman arts a work featuring flowers in a vase onits left wall- as well as framed prayer around the walls in the tradition of Ottoman mosques. Its four central pillars are topped by arches; its torah covers are silk velvet, embroidered with real gold thread; and its eternal light always burns pure olive oil.

Synagogue building to the left of the Seniyora’s doorway (as you face it) was once a synagogue, but the space is now occupied by a wholesale poultry business.

At the end of the fifteenth century, Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition began to settle in the Kemeralti district of Izmir. Over the next 300 years, the prosperity and creativity of the Ottoman Jews was notable. At its peak in the nineteenth century, the Jewish population of Izmir reached approximately 50,000.

The Central Izmir Synagogue Complex, located in the heart of the historic city center, consists of nine adjacent synagogues constructed in diverse sixteenth century Sephardic styles. Despite their non-monumental exteriors, the sanctuaries exemplify exceptional interior planning and craftsmanship. Perhaps the most distinct characteristic of the Izmir synagogues is the unusual “triple arrangement” of the Torah ark, which creates a unique harmonious ambience. The central positioning of the bimah (elevated platform) between four columns divided the synagogues into nine parts.

The Jewish population of Izmir has been rapidly decreasing since 1944. Today, less than 2000 Jews live in the city and the community responsible for the Synagogues lacks the resources to maintain or revitalize the complex.

Senora Shul was named for Dona Gracia Mendes Nasi

Izmir’s Senora Shul was named for Dona Gracia Mendes Nasi, an incredibly powerful, wise, and righteous woman. Born in 1510 to a wealthy family of Anusim in Lisbon, she was wed to her uncle Francisco Mendes, another crypto-Jew, who the King of Portugal at the time said was the wealthiest man in Lisbon. Their family developed a financial empire, with banking houses across Europe. Their fleets brought spices from the Orient. When Francisco died, this vast conglomerate was left in the hands of his young widow and their infant daughter.

Dona Gracia moved to Antwerp and quickly established an escape network for Jews from Portugal, who were forced to convert or die. As a secret Jewess herself, Dona Gracia always arranged backup escape plans during her meetings with the world’s royal and influential figures.

By 1538, when her brother-in-law died, this twenty-eight-year-old woman was solely responsible for one of the larger family fortunes in the world. Naturally, her wealth brought influence. This attention from the likes of the pope, Henry of France, Charles of Spain, and Suleiman the Magnificent kept her busy deflecting marriage proposals. Escaping from Antwerp, she made her way to Venice, but a dispute there forced her to flee to Ferrara, Italy. Interestingly, during her stay there, the first printed Tanach with a Spanish translation was published, and is known as the Ferrara Bible. Its more formal name was, “The Bible in the Spanish Language, Translated Word for Word from the True Hebrew by Very Excellent Literati, Viewed and Examined by the Office of the Inquisition with the Privilege of the most Illustrious Lord Duke of Ferrara.”

The importance and expense of such an undertaking should not be minimized, as it finally gave the Anusim the Tanach in a language they could understand. It is no wonder that the second printing is dedicated to Dona Gracia. It was in Ferrara that she finally publicly renounced Christianity and announced her Judaism. Once again she fled, and in 1553 she made her way to Turkey. In Constantinople, Dona Gracia used her vast fortune to support scholars, yeshivos, and the printing of Jewish books.

One final incident deserves mention. In 1555, the newly elected Pope Paul IV decided to rid the papal states under his rule of the Anusim, now openly following Judaism. About 100 Jews in the port city of Ancona were imprisoned and tortured by the Inquisition and sentenced to be burned at the stake. Dona Gracia petitioned the sultan for help, but despite her best efforts, a group of Jews was burned. For the first time in Jewish history since the Bar Kochba rebellion, this amazing woman initiated a proactive defense.

Together with other Jewish merchants, she placed an international embargo on the important port of Ancona. While the embargo did great damage to the finances of the pope’s city, it ultimately failed.

Dona Gracia hoped to end her life in Eretz Yisrael, and even managed to obtain the area of Tiveria from the sultan. She then invested money developing the land. One could say it was the first attempt to help formally settle the Land of Israel in close to 1,500 years. So beloved and endeared was she that she was simply known to world Judaism as “La Senora,” or “the lady.” Rabbi Moses di Trani, paraphrasing Mishlei 31:29, referred to her Hebrew name of Chanah: “Many daughters have done virtuously, but Chanah has excelled them all.”

View Larger Map Seniyora Synagogue,

The synagogues in Izmir are mainly located in an area adjacent to the Neighbourhood of Namazgâh. This area is also the settlement place for the Jewish community.

The Jews, who settled in Izmir in 1492 and the ensuing years created their own settlement in a manner similar to the one observed in other cities, with each such group opening a sanctuary. In recognition of this Street No 927 at Mezarlikbasi is known as Havra Sokagi (Street of Synagogues). The street is called by this name because of the amount of synagogues in the vicinity.

The Seniyora is the most active of the remaining synagogues on Havra Sokak, open every morning. It’s a simple but pleasant and interesting building, almost two centuries old, with obvious historic value.

Few ruins of the ancient world tell it like it was the way two archaeological sites within easy reach of Izmir do. Ephesus is considered by many to be antiquity’s best-preserved city. And to tread the huge blocks that paved its streets, to see its marketplace, its public sanitary facilities, its twenty-four thousand-seat amphitheater, is to have some genuine sense of stepping back through time. Yet only one tenth has been excavated so far, and the heavy money says that when it is, a synagogue will be unearthed.

That there were Jews here is almost unquestionable, since the apostle Paul preached in Ephesus and his first targets were the Jewish congregations. Concrete evidence exists in a form not yet officially explained. On the main street of Ephesus stand the remains of the library of a second-century C.E. governor-general of a large portion of Asia Minor. At the library’s entry stand eight columns. And on the top step, the seventh up from the absolute bottom of the flight, near the base of the third column from the left, facing inside, is a clearly defined scratching in the stone of a menorah.

The other site is far larger and grander, though it does not bear any symbol so defining as the menorah.

This is the second-century Roman synagogue of Sardis, once the capital of the Kingdom of Lydia, ruled between 560 and 546 B.C.E. by the wealthy King Croesus, the first monarch to mint coins. The synagogue, not much shorter in length than a football field, features numerous remaining mosaic floor patterns; a line-up of six columns along each side; and two altar areas, topped by inverted V’s, obviously influenced by Greek architecture. Just outside the synagogue, along one wall, was Sardis’s business center, with many Jewish proprietors manning the “shops” now separated by crumbling stone partitions.

In Izmir itself, a short flight or an eight-hour drive from Istanbul, several traces remain of a community that, when the town began its seventeenth-century development as a center for Mediterranean commerce, had been one of the most important Jewish settlements in the Ottoman Empire. Of the 15,000 who lived in this pleasant seaside city before 1948, only about 2,000 remain.

Though they now reside primarily in the prestigious Alsancak area, where they have built a new synagogue, Shaar HaShamayim, the primary sights are concentrated in and around the bazaar, once the community’s heart. In the rundown area edging the bazaar entrance near the municipal parking lot and opposite Emlak Bankasi, Shabbetai Tzvi was born. In the bazaar is a street now known simply by its number, “927.” But not long ago, this was called Havra Street, for the nine synagogues and many Jewish shops that once dotted the way.

Now only two synagogues arc easily seen. One is the Senora Synagogue, at number 77. An airy sanctuary, whose dominant color is white, though trimmed with muted turquoise and gold, it boasts a piece of Ottoman art a work featuring flowers in a vase on its left wall as well as framed prayers around the walls in the tradition of Ottoman mosques. Its four central pillars are topped by arches; its Torah covers are silk velvet, embroidered with real gold thread; and its Eternal Light always burns pure olive oil. The Shalom Synagogue, at 38C, off a passageway filled with shoes, heels, and shoe trees, is wildly colorful.

Almost everything, from the walls to the benches, is bright turquoise. Cushions covered with a bright floral pattern pad the benches edging the walls and running perpendicular to the ark. The floor is covered with Turkish carpets, some of which display minaret motifs. But most striking is the ceiling painted, as the ceilings of wealthy Ottoman homes were, with geometric kilim designs and colors meant to look like carpets.

A narrow walkway with merchandise samples hanging overhead, “927” runs into the larger Anafartalar Caddesi and, at number 331, the Metin Sasson Jewelry Shop, one of about one hundred shops in the bazaar, is still owned by Jews.

Driving south along the waterfront to the erstwhile Jewish neighborhood of Karatas leads not only to the Beth Israel Synagogue, Mithat Pasa Bulvari 245, but also to the “Asansor” or elevator, the first in Izmir, constructed in 1907 by Nissim Levy. Levy made his fortune by charging for the ride from one street to another one on a higher level, one hundred feet up a cliff side. Though the old water-run contraption has been replaced and the freestanding building recently refurbished (there’s an excellent view of the waterfront from the top), a sign above the entrance still proclaims the structure’s provenance in French and Judeo-Spanish, written in Hebrew characters, with the Arabic “Marshallah” (“With God’s Blessing”) above in calligraphy.

The synagogues are interesting unfortunately the Jewish community is fading rapidly.

It was surely worth while going, I was lucky enough to be able to go into a couple of the synagogues and the most beautiful part is knowing the history of the synagogues and finding out how the Jews from Spain came to Turkey.

Our guide told us about the Jews coming from Spain and their lives in Izmir. She took us to Seniyora Synagogue. It was very interesting.

We were happily wandering around the Market and asked several people for directions to the Synagogue. Out of nowhere a man appeared and escorted us! He unlocked the Gate and let us in the the Beautiful Synagogue – Free! Just awsome!