Mustafa Pasa (Mustafapaşa) was inhabited by Greeks of Ottoman citizenship (who named it Sinassos) of Turkey until 1923, who left the region when the population exchange took place. Mustafa Pasa, 6km to the south of Urgup, was inhabited by Greek Orthodox families until the beginning of the 20th century. The houses dating back to the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries display fine examples of stonework.

It is a quiet place, with some nice houses from that period, some restored or under restoration. It is off the beaten Capadocia track, yet within easy reach of Urgup and Ortahisar.

Gomede Valley, to the west of Mustafapasa, resembles a small version of the Ihlara Valley. As at Ihlara, the walls of the valley house churches and shelters carved from the rock, and a river runs through the valley.

The important churches and monasteries around Mustafa Pasa are, the Church of Aios Vasilos, the Church of Constantine Elene, Churches in the Monastery Valley and, the Church of St. Basil and Alakara in Gomede valley.

There is also a Medrese built during the Ottoman period and displaying fine examples of stone masonry and woodcraft.

Mustafa Pasa Village, Cappadocia,

Mustafapasa Village is one of the nicest villages in Cappadocia. In the last century it was the centre of Cappadocia and rich ottomans built their splendid mansions here.

The whole village consists of such mansions and they are all built from square stone blocks of tufa. There are wonderful wall paintings and dainty relief works inside the mansions.

The village was mostly inhabited by greek speaking rum who also built many of the churches.

This is one of a number of chapels that have been painstakingly carved into the steep rock face of the Goreme Valley, just west of the small town of Mustafapasa in Cappadocia.

Looking back at the fissure through which I have just entered, a staggeringly beautiful panorama is framed against the crumbling walls. A vast ochre-and-white-striped ridge snakes through the dry plains like a huge stone wave – but one topped with looming, stratified monoliths. The result of thousands of years of wind and rain erosion, the startling rock formations and magical “fairy chimneys” of Cappadocia, in South Central Anatolia, make for a spectacular landscape.

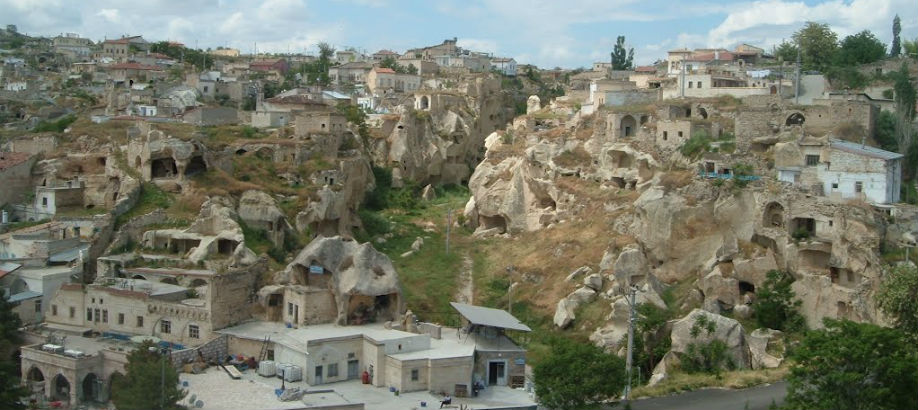

Mustafapasa is no different, except in this town the warrens of grottos are hidden behind statuesque neo-classical façades. Unmistakably Hellenic in style, the town is celebrated throughout the region for the ornate carved stonework of these beautiful houses. On some, a date or name has been embroidered into the decorative stonework in Greek letters; subtle clues that allude to the thriving Greek Orthodox community of wealthy merchants who settled in the town in the late 18th and 19th centuries.

The tour groups that whizz through the town invariably pause to take snapshots of Mustafapasa’s magnificent Greek houses. In a landscape where many villages seem to evanesce into the amber cliffs at a distance, retreating into the dramatic rock formations until only the hollowed mouths of windows and doors remain, such calculated ornamentation is an arresting sight.

However, moving past the relative bustle of the town square, it becomes clear that very few of these old Greek houses are occupied. The vast majority have been left to the mercy of the weather for decades. Doors hang off their hinges, revealing vacant interiors devoid of life, bar the stray cats that wander freely through the barren rooms and open staircases.

The hotel my husband and I stayed in was similarly inscrutable. A rambling sandy-coloured maze of a place, the Monastery Cave Hotel’s smooth exterior belies a multilayered labyrinth of sunny terraces and small cave rooms. Until recently, these atmospheric rooms were used as monks’ cells and the corridor walls are peppered with shallow coves blackened by candle flame.